Violence

Lacey Meek

Fire consumed the pages. Flames lapped up the paper greedily, and the white sheets curled in on themselves in blackened pain. There was something final about the action. It was victory. A small victory, but the first one. This moment was all the sweeter for it. They treated us like animals, like pack mules. It was as though our race was bred solely to serve as stepping stones for them. We did all of the work, and they gained the rewards. Today we were taking a stand against it. I had stood in the masses, had tossed my pass into the grasping flames and watched it burn. For this moment at least, I could close my eyes and imagine that I was free of the curse of apartheid. This must be what it feels like to be white.

We are a species that is infatuated with success. We strive to pull ourselves to the top, towards prosperity, always reaching for perfection when it will always be just beyond our grasp. Sometimes in that struggle, we forget about others or even purposely drag them down in order to make us feel superior. This creates an unjust situation. Unjust situations are everywhere, and range on a very wide scale. This scale varies from Galtung’s latent violence where the attacker simply thinks of committing violence, to the cruelties of apartheid and inhumanity of murder. Similarly, there is a wide range of solutions that will change these unjust situations. What is the best solution? This is defined by the person answering the question, and their definition of the word “best.” My views are this: although violence may be the quickest path towards the resolution of an unjust situation, we see that far more often non-violence is the more effective of the two options.

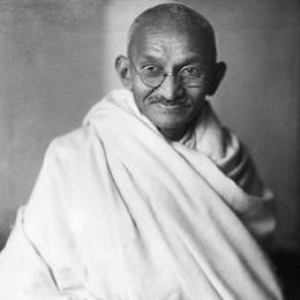

In The “Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” author Ursula LeGuin says: “The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting… But to praise despair is to condemn delight, to embrace violence is to lose hold of everything else.” (2) A similar idea is pointed out in the “Active Nonviolence” writing: “Many mistakenly think that power comes from violence and that it can be overcome only by greater violence. Gandhi said, ‘strength comes not from physical capacity but from an indomitable will.’” (9) I believe that these form the basis for all acts of violence. In our seminar, I was shocked to hear just how many people felt violence was the better route simply because it was the fastest way to establish change. This sort of reasoning is what causes our belief that power is violence. Just because something can be accomplished quickly doesn’t mean that the method is powerful. It means that the method is efficient. This can become an easy out that we use to explain why we’d rather resort to violence first. Of course, aggression isn’t always the worst way to resolve a conflict: America was the result of a violent resolution, and for better or worse, it is still around after many long years. This is also seen in Libya, which has recently suffered heavy fighting between the government and its people. Currently they are on the road to rebuilding their country in a fashion more acceptable to them. This may last for a couple of years, though hopefully longer, depending on the government they build and outside forces. Sometimes violence is the best resolution. However, more and more it seems that we lose the ability to discern when violence is needed from when it is the easiest out.

Force is often unnecessary and frequently a useless course of action for many reasons, but we tend to look past them when considering it as an instrument of change. Chief among these reasons is violence’s inclination to create short term resolutions. This is most likely caused by underlying tensions that linger even after the conflict is supposedly resolved. These short resolutions are also caused when we lose control, as is explained in the “Active Nonviolence” writing: “Gandhi taught that one must not work for a noble goal by evil means, for means and ends are interconnected just as the seed is to the tree.” (9) This is very true. If we lose control of the means when wielding violence, we lose control of the ends, which can cause their instability. If we resort to peace rather than war and conflict, then we choose a way that requires patience. With patience we may control the ends which will secure long lasting terms, or at the very least, more stable ones. We choose to build our relations with others, rather than destroy them, and this will discourage violence in the future as well.

Peace can also be used to gain support from outside forces. In fact, it may be one of the strongest ways to gain their respect and place pressure on the oppressors. In the movie Gandhi, there were two strong examples of this: Gandhi burning the passes, and the opposition of the closing of a salt mine. When Gandhi burned passes in opposition of a new British law on the Indians, he was beaten repeatedly. This was one of his first demonstrations, and he gained quite a bit of respect from others. (Gandhi, 1982) Even though he was put in the hospital, jailed at least three times, and nearly killed by his fasting, Gandhi’s policy of peaceful opposition, and refusal to lash out when provoked earned him great respect and he earned a following rather quickly. At one point, when he was in jail, the British closed an Indian salt mine. The workers opposed this and lined up in front of the gates to go to work. They marched to the guards, and line after line was brutally beaten back. Yet they refused to fight, and this became a source of extreme fascination to the outlying countries. (Gandhi, 1982) The Indians’ resolution was first really taken into account by the rest of the world due to its nonviolence, giving them more support and putting more pressure on Britain to give India its freedom.

One of the most important lessons to be learned when dealing with violence is that it only breeds more violence. In support of this theory, Gandhi said that: “an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind,” (Gandhi, 1982). The theory of fighting fire with fire doesn’t apply to violence. Violence will only grow and spread until the world is at war with itself. Only peace can break the cycle of violence, and it will never end unless we make an honest effort to try. Peace will douse the fire rather than fan the flames, relieving tensions and building stronger relationships.

The fires will continue to rise though. It seems to be a growing trend in human nature to allow them to go unchecked. However with peace we can fight back, for a society free of the flames of unjust situations. If we continue with violence, we will quickly learn that speed is not the only factor that determines the quality of a resolution. What use is speed if countless lives are lost? What promise is there in violence that it will even be quick? Best, for me, is determined by its longevity, stability, and lack of loss. Love is far stronger than hate, and there is always a peaceful solution to conflict. We are not built to destroy each other, and no person should have ownership over another. This is why peace is the best way to change an unjust situation in my eyes.

Works Cited:

Gandhi. Dir. Richard Attenborough. Perf. Ben Kingsley, John Gielgud, Candice Bergen. Columbia Pictures, 1982.

Mandela, Nelson. “An Ideal for which I am Prepared to Die.” Opening his trial. Supreme court of South Africa. Docks, Pretoria. 20 April. 1964.

Deats, Richard. “Active Nonviolence: A Way of Live.” Active Nonviolence, The Fellowship of Reconciliation. Fellowship of Reconciliaion, 1991.

LeGuin, Ursula K. The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas. New York:Harper and Row, 1975.